MOUNT HOPKINS, Ariz. — There is no Border Patrol in space. But the very earthly cat-and-mouse game between smugglers and America’s border agents is affecting the exploration of space, lighting up the nighttime sky in southern Arizona and making astronomers strain even harder to figure out the mysteries of the universe.

Lights

on Earth Impede Arizona’s Eyes on Space

By MARC LACEY

Published: May 19, 2011

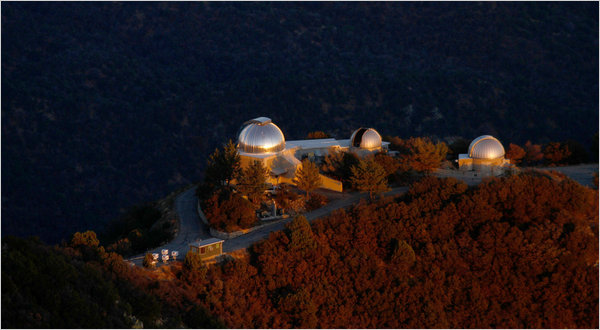

Arizona is an astronomy haven with an array of prestigious observatories taking advantage of the state’s dry weather, minimal cloud cover and dark skies. But the state’s astronomers worry about a variety of threats — border enforcement among them — to the pristine conditions that have allowed them to discover new planets, gain important insights into how the universe functions and generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually in economic return.

Drug smugglers and illegal immigrants making their way north are sometimes visible to astronomers at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory here who take a break from gazing skyward to look around the rough, wooded terrain. But it is not the outlaws that affect their work as much as the authorities who are after them.

A Border Patrol helicopter shining a blinding beam on a group of suspects runs the risk of interfering with valuable machinery trained upward, like the four massive telescopes, known as Veritas or the Very Energetic Radiation Telescope Array System, that measure gamma rays. “It’s happened,” said Dan Brocious, spokesman for the observatory, which is jointly run by the Smithsonian Institution and Harvard University and has operated atop this mountaintop since 1968.

The Border Patrol says that it tries to steer its helicopters clear of observatories, but that frequent staff turnover has occasionally resulted in missteps.

The checkpoints that the Border Patrol has set up around southern Arizona, complete with high-powered beams to light them up at night, have been another sore point, prompting meetings between area astronomers and agents and a pledge from the Border Patrol to reduce the wattage. The lights are among the brightest points now visible at night in the area, astronomers say.

But even car headlights can be a problem for sensitive stargazing, which is why signs along the winding road that leads to the observatory urge drivers to use only their parking lights after dark. The nearly 50 years since the Whipple Observatory was built here in the Coronado National Forest have brought retirement communities, shopping malls and assorted other developments to the area, all of which have boosted the light levels detected by astronomers scrutinizing the sky.

Wildfires are another concern in the remote areas where the observatories are located. In 2005, a fire that was caused by a lightning strike came within less than a mile of the Whipple Observatory, which had to be evacuated until firefighters, aided by a sudden rainstorm, were able to control it.

Earlier this year, a fire west of Nogales prompted a brief closing of the MMT Observatory, which is also atop Mount Hopkins. The observatory’s large telescope, 21 feet in diameter, is the 14th largest in the world and is sought after by researchers looking into deep space. Besides less-than-optimal viewing conditions caused by the fire, operators were worried about the buildup of ash on the lens.

Well after the sun has set, from 8,500 feet up on Mount Hopkins, the second-highest peak in the Santa Rita Range, one can observe both the majestic nature of the universe and the threats to the stargazing that has long gone on here. Competing with moonlight are street lights, traffic lights, security lights and innumerable other forms of illumination. To the north is the Tucson skyline, a vast expanse of soft white and yellow light, which has been managed by municipal dark-sky restrictions and has not grown in intensity anywhere near as fast as the population.

Astronomers are a powerful lobby here when it comes to keeping the skies dark at night, and nearby Tucson is the headquarters for the International Dark-Sky Association, which attempts to press for light restrictions around the world. “Light pollution is an issue all over the world,” said Paul J. Groot, an astronomer from the Netherlands who was conducting research on the source of X-rays from other galaxies at the MMT Observatory this week. “It limits our deep observation of the night sky.”

An open-pit copper mine that is proposed for an area southeast of Tucson and would operate around the clock has alarmed dark-sky advocates, even though the Rosemont Copper Company has said it plans to abide by Pima County’s restrictions on light pollution.

“When these observatories were selected, there was hardly anyone living here,” Mr. Brocious said atop the mountain as darkness and light seemed to compete in all directions. “Tucson was a sleepy little cow town back then. There’s nothing sleepy about it now.”